Want to Shift from being a Data Monitor to being a Data User? Here's How.

A couple in a TV commercial calls a termite inspector to determine if their house has termites. The inspector confirms that the house does indeed have a termite problem when he observes the couple’s daughter fall through a termite-damaged stair. Much to the dismay of the couple, the inspector says he is only a pest monitor and they need to call someone to exterminate the termites.

In

this ad from LifeLock [1], the company exclaims they

not only monitor problems, but also fix problems when they find them. While

I scoff at this commercial, it struck me recently that

L&D reporting shares a lot of similarities with that termite pest monitor. We

spend too much time monitoring our results rather than using them.

In an admittedly unscientific poll I conducted this month on LinkedIn (n=30), 87% of respondents used less than half of the data in their reports for decision making. I suspect the people who generate these reports believe their output is useful to someone, otherwise they wouldn't generate it. But the data (and my client experiences) suggest that we spend a lot of time monitoring data rather than using it.

Why We Become Data Monitors

I doubt anyone aspires to be data monitor. You probably feel

a tad guilty about ignoring that 20-page slide deck that shows up regularly

in your email. In the midst of all those

urgent and critical to-do’s, the data in those reports likely feels irrelevant

and not particularly helpful. To protect the little discretionary time available,

you tell yourself: “If there is something really

important in that report, I’m certain someone will let me know.”

We often

unwittingly become data monitors because of systemic organizational problems:

- Leaders unrealistically expect us to manage or oversee a large number of measures

- Most data in the reports isn’t pertinent to our role or accountabilities (as my little poll suggests)

- The important insights are not immediately visible

- The data is static and often backward looking

How to Shift from Being a Data Monitor to a Data User

In David Ulrich’s excellent 2015 book, “The Leadership

Capital Index” [2] he writes that organizations need to do two important things

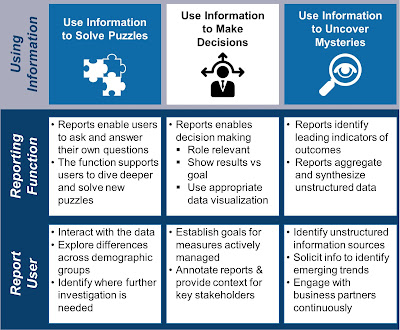

with its information (See the infographic below):

- Manage the information, specifically its flow, transparency and quality

- Use the information not only to make decisions but also to solve puzzles and uncover mysteries.

I’m not going to discuss the management of information in this blog other than to state that it is the foundation required for effective data use. Instead, I will focus on the use of the information.

Use information to Solve Puzzles

In an article by Millward Brown [3],

Phillip Herr wrote, “When we solve a puzzle, we end up with a specific answer —

one that is quantifiable, comparable to answers to other puzzles treated in a

similar manner, and invariably a go/no-go decision.”

In L&D, we solve puzzles frequently. We may ask, “Did

the senior directors get more value from the leadership course than the

executive directors?” “Did our data suggest that employees with high manager

support were more likely to improve performance vs employees with low manager

support?” Through basic statistical

analysis, we can get straightforward answers to these puzzles. We may need

another level of analysis to uncover why

senior directors get more value from the course, but we now have direction and a means to understand both the

“what” and the “why”. Our answers to

these puzzles should help inform our decisions and possible actions.

L&D organizations with whom I work do a solid job of asking questions and solving puzzles.

However, if you suspect your organization is more prone to monitor rather

than use data, consider these approaches:

- Explore where you exceed as well as fall short of your goals. Ask questions that uncover the factors that drive successful outcomes.

- Identify how results vary by key demographics such as geography, course, delivery vendor or location. When you separate data by demographics you can uncover specific areas that warrant further investigation or even help you solve the puzzle.

- Look for correlations of key variables. Do employees derive more value from their community of practice when the content is more readily accessible? Is value more highly correlated with the number of opportunities to interact with other community members? Correlation data can help you explore relationships that are not visible through trend or comparison analyses.

Use Information to Make Decisions

In almost everything we read about data (big or small), we

are reminded that we should use information for decision-making. The

challenge is that most reports give us information but insufficient

insight.

If “information over insight” describes your organization,

you should consider how to restructure your reports to ‘speed time to insight”

and ultimately decision making. Consider the following approaches:

- Ensure reports are role relevant. If you manage L&D leadership programs, the reports should highlight the data relevant to those programs you specifically manage. You should not have to hunt and dig to find what is specific to your programs. If you receive data via a dashboard, when you click to the site or app, it should know who you are and display your content on the first screen.

- Display all results against a goal. Your performance against goal will inform your decisions and actions. The comparison (with appropriate color-coding or symbols) makes it easy to highlight large variances that require attention.

- Annotate your reports. Context is critical; add comments to explain the cause of a deviation from the trend or goal.

- Use appropriate data visualization methods. Learn how to display data; avoid chart junk or difficult-to-read displays to ensure the message is clear.

Use Information to Uncover Mysteries

I commonly see leaders use information to solve

existing problems and make decisions. What Ulrich makes clear is that problem solving and decision-making is not enough. Competitive

advantage springs from seeing patterns and themes that highlight emerging

problems or opportunities. This is the territory of "Big Data" and where you need to uncover mysteries.

Unlike puzzle solving, “when dealing with a mystery, no one

can address the problem directly; someone has to discover the pattern first.

The problem with mysteries is that sometimes leaders don’t even know the right

questions to ask to explore them.[4]”

How do we identify the mysteries we should solve? First,

connect the dots across multiple data sets.

For example, what is the relationship between engagement and the use of

social/informal learning resources? Second, identify how to mine unstructured

data such as emails or online discussions. Third, stay attuned to market and

industry shifts and use your own data to assess if your organization is keeping

pace.

Here are specific actions you can take to identify important

mysteries to solve:

- Identify sources of information and listening posts such as discussions between performance consultants and their business clients as well as presentations or blogs by industry leaders or researchers.

- Quarterly, identify themes from your listening posts. Discuss articles about shifts in the industry or a success story from a company you admire. Develop hypotheses and then identify how to confirm or refute them in your own organization.

- Incorporate insights into the annual planning cycle. Where should you allocate funds to conduct a proof of concept of a new process or method? Where do you need further insights about how your employees learn or consume content?

Who owns the shift from monitoring to using data?

If the L&D measurement and reporting team were solely responsible for moving the organization from being data monitors to data users, you could simply pass along this post and ask them to make it happen. But, like that termite problem, it’s not just about the termite exterminator. The homeowner has some responsibility as well.- Measurement and Reporting (M&R): To shift the organization from monitoring to using reports, the M&R function needs to rethink its approach to data and reporting.

- Eliminate one-size-fits all reporting

- Enable users to interact directly with the data to ask and answer questions, drill down and explore the data beyond the surface

- Guide L&D to focus on the critical few measures to manage the business. Help L&D align its measures to its business priorities

- Coach L&D to use a balanced suite of measures. Include a mix of both leading and lagging indicators. Report on not just efficiency measures but effectiveness and outcomes as well. With a balanced suite of measures, report users will be provided with a holistic view of their performance.

- Report users:

- Develop goals for every measure you actively manage. (I can't repeat this enough.) Goals define what ‘success looks like’ and help focus your attention in those areas that need course correction.

- Schedule time to reflect on the data, ask questions and explore insights. Confirm or disprove rumors or ‘conventional wisdom’ through your analysis.

- Establish a process to synthesize and interpret unstructured information. Qualitative and unstructured data has an important role to play. Ensure you bake it into your data use regime.

Summary

Being a data user is lot more rewarding than being a data

monitor. Make data use a priority by reviewing your reports regularly with your immediate team. Discuss insights and assign follow-up. With the right data, the right type of report and thoughtful review, you can hone your analytical thinking skills and improve how you lead and manage your function.

[1] I do

not use the LifeLock product or invest in the company

[2] "The Leadership Capital Index", Dave Ulrich, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2015, http://amzn.to/2dKATQH

[2] "The Leadership Capital Index", Dave Ulrich, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2015, http://amzn.to/2dKATQH

[3]

Solving Puzzles Delivers Answers; Solving Mysteries Delivers Insights. 2011, http://bit.ly/2dQ9kmb

[4] "The Leadership Capital Index", Dave Ulrich (see source above)